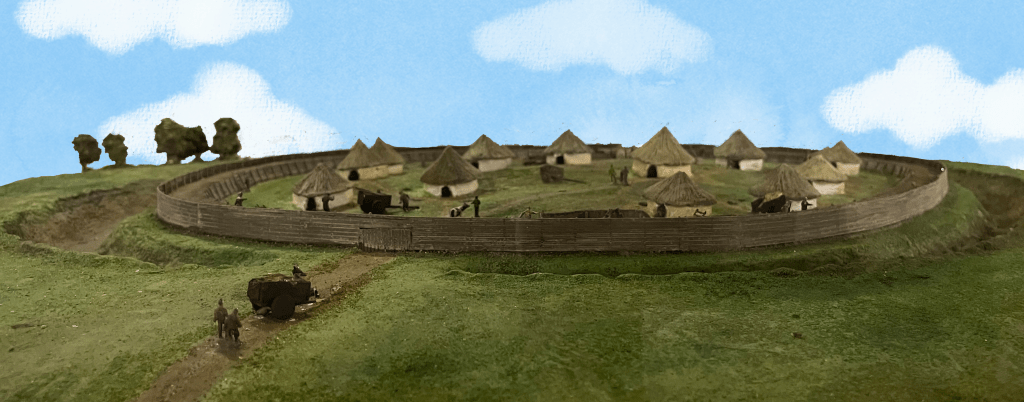

The year is 4 BC. Ancient Britons are mulling around their hillfort in Hunsbury, producing metalwork and pottery whilst enjoying the fine arts of poetry and music. Life is simple; defend the hillfort and trade goods. Fast forward 2,500 years and find a country park surrounded by a housing estate. Trees and shrubs grow where the defensive ditch once was, and the banks have eroded; now mere whispers of their former glory.

Hunsbury hillfort was one of the thousands of defended enclosures across Britain. With the dispersion of Celtic people across Europe, many tribes eventually settled in Britain and remained there until the Roman conquest. Tribal tensions meant that allied clans grouped and built hillforts to defend themselves from attacks.

There are at least six hillforts in Northamptonshire, with Hunsbury as one of the most well-known. Despite the eroding effect of time and the damage from ironstone quarrying, multiple archaeological digs and surveys have revealed what living in the local hillfort was like.

People likely occupied the hillfort from 4 BC to 1 BC, and it would have taken the form of a standard hillfort with several one-roomed roundhouses. It would have also been surrounded by a ditch and a timber-laced rampart. Historians estimate that the site was abandoned near the end of the first millennium, before the Roman conquest. However, traces of Anglo-Saxon pottery suggest that the hillfort may have been occupied during this era.

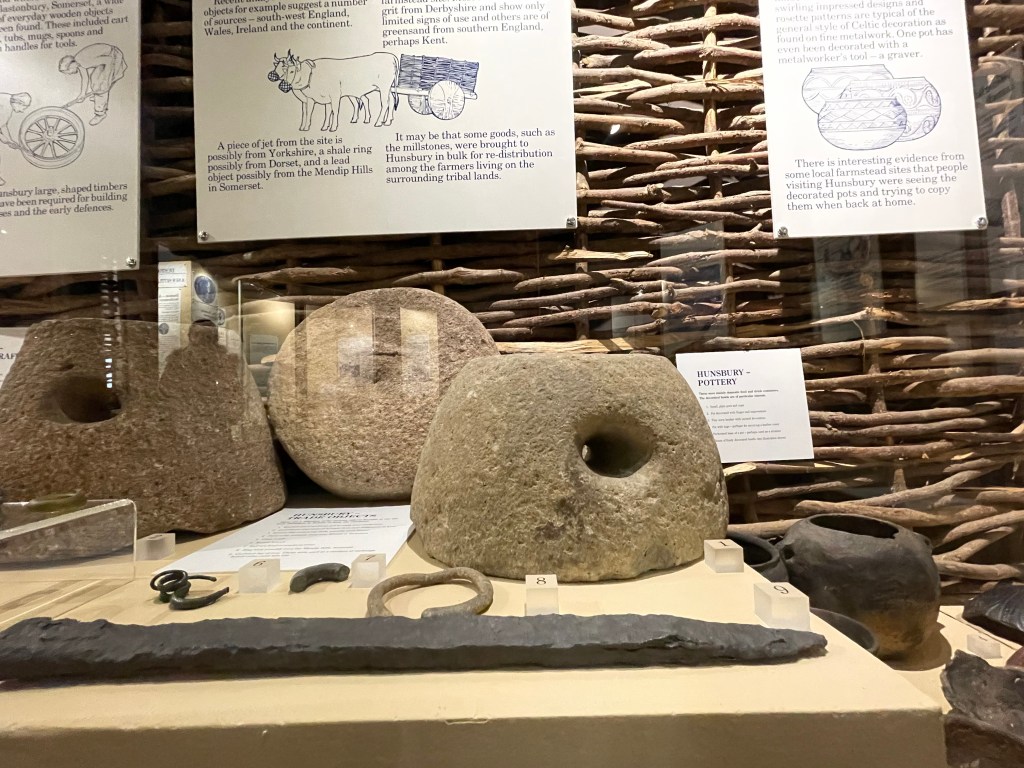

The fort now takes up around 1.6 hectares, and its ditch is estimated to have originally been eight metres deep. Northampton Museum and Art Gallery currently hold a vast array of objects found in previous digs that form one of the largest collections of Iron Age artefacts in the country. One of the most popular finds was rotary querns, an item comprised of two flat stones placed on top of each other used to grind grain to flour. A dig in the 19th century, conducted by local historian and antiquarian Sir Henry Dryden, found 159 of them. Andy Chapman, Honorary Secretary of the Northampton Archaeological Society, said: “The rotary querns are far more than what would have been required for daily use, indicating that the hillfort served as a collection and distribution centre for rotary querns. These were manufactured at several production centres, all at some considerable distance from Northamptonshire, making them a valuable trade item.”

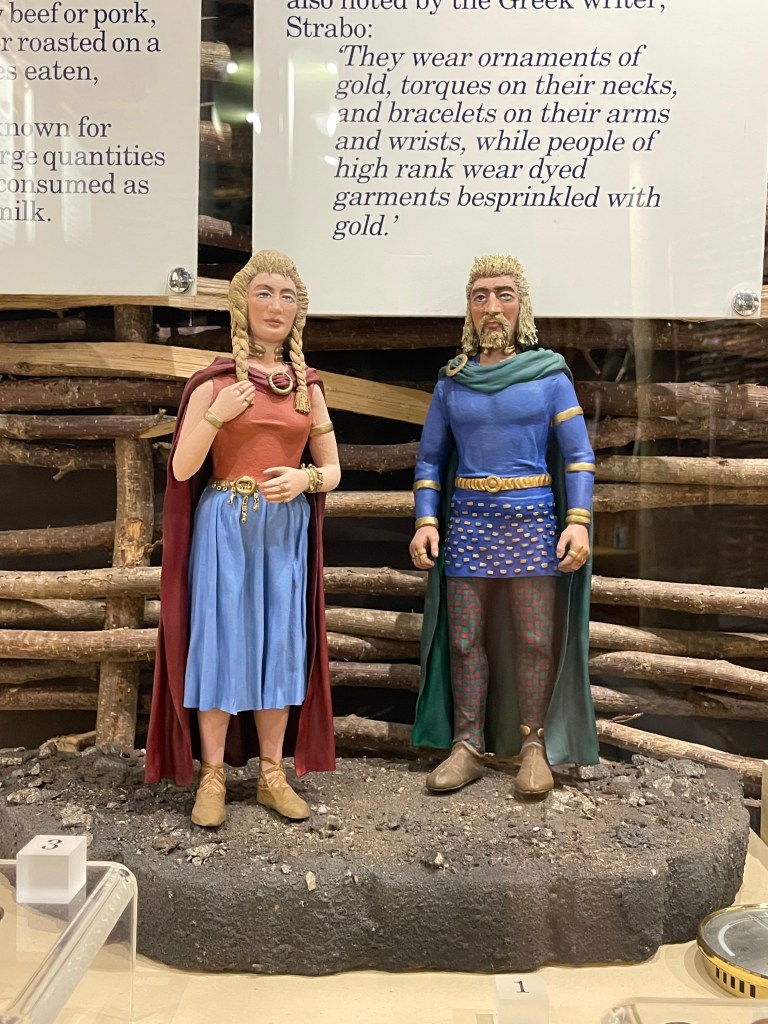

As well as functioning as a trade centre, Andy Chapman suggests that Hunsbury hillfort was also the home of a notable figure. He said: “The site may also have contained a chariot burial, which indicates the presence of a high-status individual, a local tribal chieftain perhaps.”

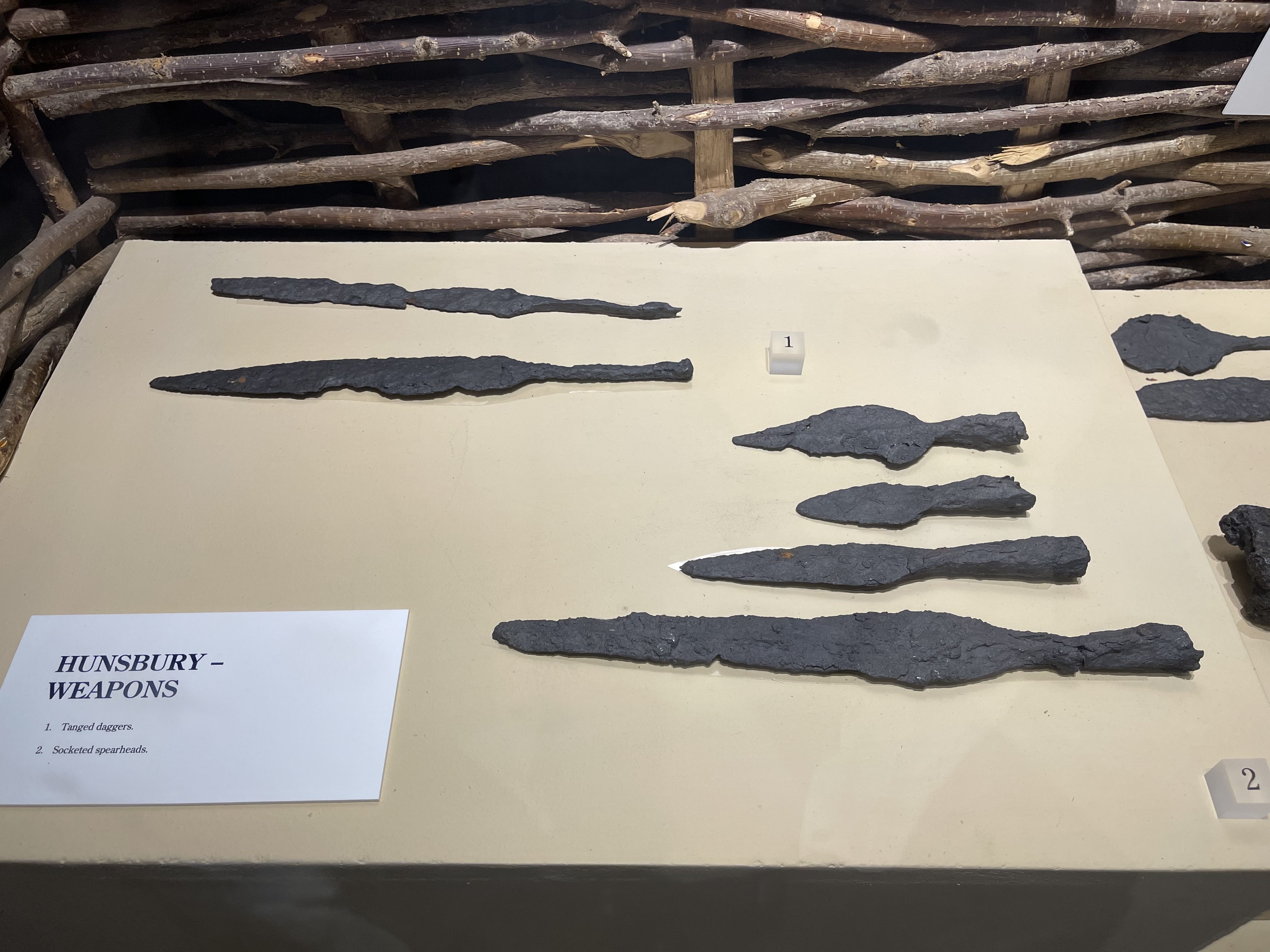

Other items recovered include bronze brooches, pottery, glass, iron weapons, tools, and domestic items made from bone, antler, iron and bronze. The ‘Hunsbury Scabbard’ was also discovered, assumed to be the first of its kind, and later replicated in other parts of the country.

In terms of excavations, the hillfort has seen many archaeologists come and go. The first proper excavation was carried out in 1952 by Professor Atkinson when sections were cut across the bank and ditch to the east and north-east. Later, in 1988, local archaeologist Dennis Jackson examined an area of the bank to the north and calculated radiocarbon dates. However, 19th-century ironstone quarrying damaged much of the hillfort’s interior, limiting further archaeological inspection. The hillfort’s eventual transformation into public parkland occurred in the early 1970s with the introduction of footpaths and vegetation. This accelerated the rate of erosion and damaged the site further.

Future plans for the hillfort are still uncertain. Andy Chapman said: “It is likely that many pits and other features survived. There is, therefore, a small part of the interior that is relatively undisturbed and which could be excavated to provide further finds and an understanding of the interior.”

Since the site is classified as a Scheduled Monument, Historic England would have to grant permission before any work could begin.

A local group called ‘The Friends of Hunsbury Hill’ are also interested in preserving the hillfort and raising awareness of its uses. They particularly encourage community excavations and using the site as a venue for public events such as historic re-enactment. However, with the arrival of Covid-19, plans have been postponed for the time being.

Currently, the site is in a state of disrepair. Trees and shrubs surround the ditch and banks, with roots and woodland creatures damaging the site. Andy Chapman said: “Active control of scrub growth is needed, in particular, such things as fast-spreading blackthorn and brambles cover parts of the banks and in some places are encroaching onto the interior.”

Hunsbury Hill is … important as the largest earthwork site in the town.

Andy Chapman

Hunsbury Hillfort, though far from its prime, is arguably timeless. Despite having worn down over centuries, there are parts of it that remain, carrying the secrets from its past. Artefacts are another way the residents of the Iron Age Hillfort live on. From the way they lived, to what they made, the remnants of the ancient Britons provide us with valuable insight into the history of the Iron Age hillfort that stands in the heart of Northamptonshire.

Hunsbury Hill is therefore important as the largest earthwork site in the town.

Leave a comment