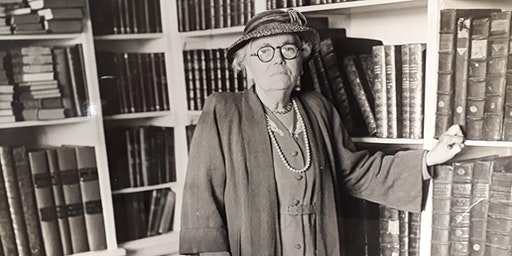

Born to Sir Herewald Wake and his wife Catherine in 1884, Joan grew up in Courteenhall, Northamptonshire. Education and the desire for knowledge were a large part of her childhood and would ultimately have a key role in her life.

By the time she was a teenager, Joan had already honed her role as a collector. Local historian, Neil Lyon, said: “She was like a magpie, collecting any photograph she could find.”

Her habit of keeping every diary entry, letter, and photo ensued even after she received one of the biggest shocks of the century in 1914; Britain was going to war. Joan contributed to the national war effort by volunteering at a military hospital in Aldershot for a few months. She later trained as a midwife under the Northamptonshire District Nursing Association at the age of 32.

However, it was on December 10, 1920, when she founded the magnum opus of her career, the Northamptonshire Record Society. Suggested to her by leading academics, Joan assumed the role of honorary secretary and spent the next 43 years voluntarily charging up and down the county in search of Northamptonshire’s lost history.

In her 43 year-long term as honorary secretary for the society, Joan collected centuries’ worth of records which needed constant re-housing due to their rapid accumulation. Playing the role of the archaeologist, Joan uncovered and analysed documents that were dusty and yellow with antiquity before hauling them back to their home in Abington Street Library.

In May 1935, for example, she was tasked with clearing out a solicitor’s attic in Daventry. In her diary entry, she said: “After much persuasion, I was allowed to go up into the attic in Daventry. I found the whole floor two to three feet deep in a promiscuous heap of documents – two centuries of them I would say, smothered in dust and dirt…It was like an archaeological dig. I have summoned two hefty lads to help me put the lot in sacks.” On this day alone, Joan retrieved 76 manuscripts and deeds back to Northamptonshire.

Her determination was only one factor that she used to her advantage. Her parents provided several high-profile contacts that she used to gain access to unique and rare artefacts. In September 1930, for instance, she persuaded Lord Winchelsea to deposit 20 boxes of papers at Kirby Hall. She even managed to loan a 17th-century dress from Queen Mary and an antique shawl from the Duchess of York.

“I got a puncture on the way home off Watkins street. I stopped a gang of Italian prisoners coming along the road and got them to change my wheel.”

Excerpt from Joan’s diary, November 22, 1945

In the years leading up to World War Two, Joan was already thinking of the safety of her records. Eventually, she decided on Brixworth Hall and Overstone as the best places to keep them. The accumulation of 20 years’ worth of collections, weighing over thirteen tonnes, took six days to relocate.

Knowing that history was in the making, Joan continued to make personal records throughout the war. Her entries eloquently capture the national anxieties of the time. On June 14, 1940, she wrote: “My roses are out, and Paris has fallen. I am waiting for the Queen to speak to the French…I have just heard her and daresay you were listening too. Marvellous fellow Hitler – always keeps to his timetable…When we hear the church bells, we shall know the parachutists have arrived. Imagine the feelings of the men who made those towers simply to know they would be used to give warnings of enemies dropping from the skies.”

Throughout the period of national struggle, Joan was on her very own mission to protect Northamptonshire’s history. In May 1941, she wrote about two important collections. She said: “I forced an idolatry duke and a reluctant earl to let me get away with them.”

However, Joan Wake did not stop at personal intimidation. She was willing to climb to the very top of the pecking order to fulfil her mission. In June 1941, Joan wrote to Winston Churchill, demanding that he help save local records. Unfortunately, this was an unsuccessful attempt. Although, she did manage to snatch four and a half minutes from the BBC to raise awareness of her cause.

By the end of the war, her records were yet again in need of relocation. Joan eventually settled on the Langhorst ancestral home, where the records stayed for ten years before moving to Delapre Abbey. The collection at Brixworth Hall was moved to the County Council, which had also set up a record office around this time.

In her later life, Joan was involved in several local campaigns, including one against iron ore works in the county, and another battling for the ownership of Delapre Abbey.

On January 29, 1954, the Northampton Chronicle and Echo released the story that the council would soon demolish Delapre Abbey, as the building had no ‘aesthetic merit’. However, unbeknownst to them, Joan Wake had already set her sights on the abbey as the resting place for her records. As it was within walking distance of the town centre and the railway station, Joan believed that it was the ideal place for her collection.

With her mind made up, she embarked on a five-year-long battle against the council to protect Delapre Abbey. With local papers calling for its demolition, and country houses being knocked down one per fortnight, most assumed that Delapre would be another mere casualty.

However, after hardy persistence and the help of John Bedsham, the council eventually gave in. They agreed that if she could raise the money to restore the abbey, it was all hers.

Against all odds, Joan Wake won. At midnight on December 3, 1956, she had raised £20,000, securing the deed to the beloved home of the county records for the next 30 years.

After borrowing money from various people, including Northampton’s leading shoe firms and the Cripps Foundation, Delapre was formally opened on May 9, 1959, in the presence of a crowd of 1,100 people.

Thus, after 43 years of holding the post of honorary secretary, Joan retired to Oxford and spent the rest of her days there. Despite her retirement, Joan continued to make entries about her life. On November 14, 1973, she wrote: “I’m getting very old. I’m practically an invalid now as my legs are of very little use, but my head still works a little.”

Joan Wake died on January 15, 1974, aged 89 – only weeks away from her 90th birthday. However, Neil Lyon said: “If she had been born on a leap year then she would insist to the very end that she was only 21.”

It is thanks to this remarkable woman that Northampton can look back and reflect on its past, which would otherwise have been left buried and fragmented across the county. This is best summarised by Joan Wake herself. She said: “A place with no knowledge of, or interest in its own history is a poor, pitiful thing, much as a man who has lost his memory.”

Leave a comment