You’ve probably heard of the Great Fire of London, the infamous conflagration that swept through the heart of England’s capital in 1666, but did you know that Northampton experienced its own catastrophic blaze just ten years later?

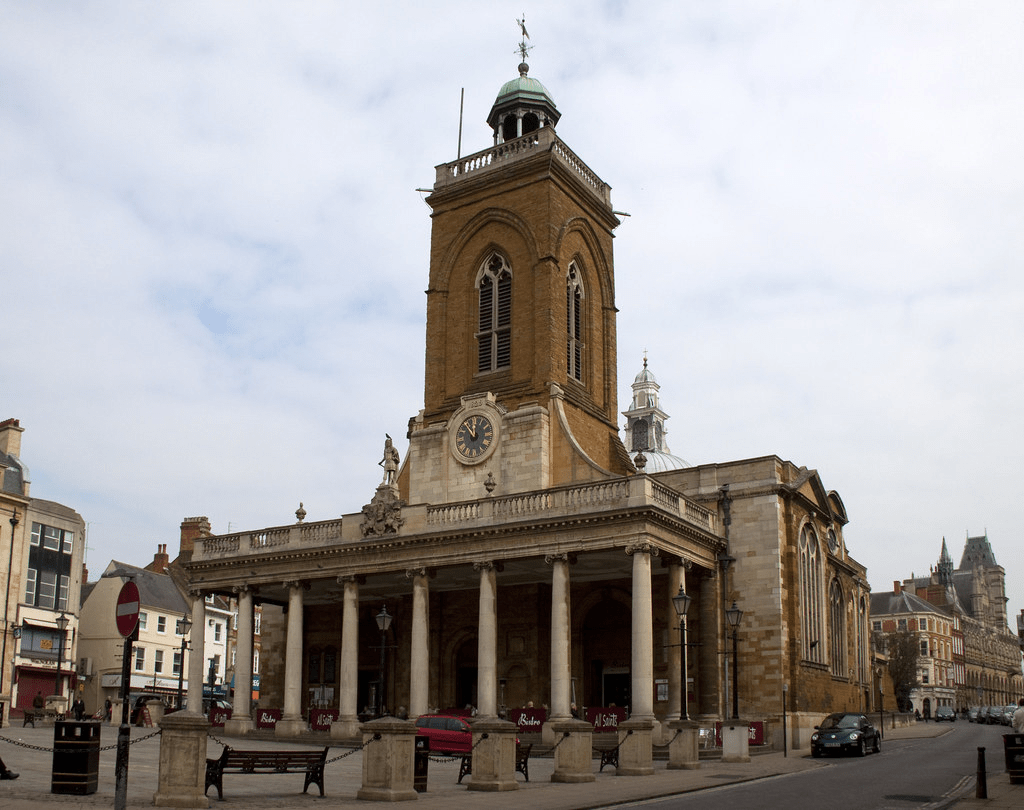

Credit: © Peter Newcombe. Photo credit: West Northamptonshire Council

Picture a regular day in September in 17th-century England. Traders are selling their wares in the Market Square, the bustling hub of trade and commerce lying at the heart of Northampton, completely unaware that, within a few hours, everything around them would be razed to the ground.

The Great Fire of Northampton is lesser known than the infamous Great Fire of London. Despite its absence from history lessons, however, it was equally as devastating and resulted in the destruction of over half of the town’s buildings.

The blaze began around 4 o’clock on September 20, 1675, caused by sparks from an open fire on St Mary’s Street. A westward wind carried the flames across timbered buildings with thatched roofs surrounding the Market Square. In line with 17th-century fashion, much of the new housing was made of wood, allowing the fire to grow into an all-consuming conflagration within just a few hours. This was made worse by the ample supply of flammable materials around the square, including corn ricks, maltings and barrels of oil and tallow.

People initially sought refuge in the Market Square, but by 5 o’clock the area was overtaken by flames. The situation quickly escalated as the strong wind carried the fire to St Giles’ Street and Derngate. Everywhere people turned, the scene was one of fiery destruction. The traders were forced to abandon their stalls and flee through the Welsh House to safety.

The overall cost and devastation to the town was immense, with the number of buildings and houses destroyed amounting to around 700 of the 850 buildings in total. Within just six hours, countless families were made homeless and hundreds of people’s livelihoods were destroyed. As the fire occurred after tradesmen had restocked at Stourbridge Fair, the loss of property was vast, equalling around £150,000.

One of the higher-profile buildings that fell prey to the flames was All Hallows’ Church. Though records describing the church’s heritage are scarce, it is believed that it had endured multiple alterations since its creation in the 11th century. It was believed to have extended down to Gold Street, however, along with its Market Square counterparts, it was quickly engulfed by the flames and burnt to ashes, leaving no trace of its original structure.

The market cross was also among the victims of the fire and, like the church, held significant historic value, dating back to the 15th century.

There was only one house that emerged unscathed from the fiery destruction, and that was No. 33 Marefair, also known as Hazelrigg Mansion, an Elizabethan townhouse from around 1580. Escaping ruin, the house remained under the ownership of the Hazelrigg family until 1831 and was later transformed into a ladies’ club in 1914.

The Town Hall also avoided serious damage, experiencing just a few licks of fire on its front staircase.

Excluding these buildings however, most of the structures in the surrounding area, comprising two-thirds of the town’s buildings, were gutted by the fire, leaving behind a scene of misery and ashes in its wake.

However, this would not be the end of Northampton or the Market Square, but a new beginning. With the help of community spirit and financial aid, the town was able to rebuild and emerge in a new and beautiful form.

The Earl of Northampton, the town recorder, took the lead in organising relief to be sent out, including packages of food and clothing. He then organised a meeting to set up a committee, leading to an Act passing through Parliament. This Act ordered the creation of a special court of record that would sit at the Guildhall and sort disputes among landlords, tenants and neighbours. It had the power to alter the layout of the town accordingly and to advise and oversee its rebuild.

The Earl of Northampton also used his influence as a friend and confidant of King Charles II to persuade him to contribute 1,000 tons of timber from the royal forests of Rockingham and Salcey. This timber was used to build All Saint’s Church in place of its burnt predecessor, following a design drawn up by architect, Henry Bell.

The King earned a reputation for generosity among Northampton residents for this and was further praised for his decision to repeal the ‘chimney tax’, which resulted in the reduction of taxes by half for seven years. As a memorandum of their thanks, a statue of him was erected on the portico of All Saints’ Church by John Hunt in 1712.

The plaque beneath it reads:

This Statue was erected in memory of King Charles II who gave a thousand tun of timber towards the rebuilding of this church and to this town seven years chimney money collected in it.

However, the King was not the only person to offer a helping hand; members of the local gentry provided homeless families places to stay, and the City of London donated £5,000. Other towns and the two universities at the time, along with various businesses also donated and contributed to the total raised sum of £25,000.

Like a phoenix, the town emerged in a completely new form and was praised by many. It was rebuilt in the 18th-century Georgian style, marking a shift in the town’s architectural development. The buildings were rebuilt with wider streets to prevent a repeat occurrence, and for many, this was an aesthetically pleasing choice.

Famous writers such as Daniel Defoe remarked on the new appearance of the town. In 1724, wrote:

“[Northampton is] the handsomest and best built town in all this part of England”

– Letter 7, Part 2: East Midlands

Thomas Baskerville similarly praised the town’s new appearance. He wrote:

“[Northampton emerged] Phoenix-like risen out of her ashes in a far more noble and beauteous form”.

-1681

In 1782, Thomas Pennant even went so far as to claim that:

“Much of the beauty of the town is due to the fire in 1675”.

– Journey from Chester to London

Overall, the Great Fire of Northampton was a double-edged sword, sparking a major architectural shift in the town’s aesthetic whilst also standing as one of the most devastating catastrophes of its past. However, from the tenacity of its residents and the generosity of its neighbours, the town was rebuilt, rising from devastation and emerging as the beautiful Town Centre and Market Square that retains its raffish charm to this day.

Sources:

“Great Fire of Northampton.” Wikipedia, 3 Aug. 2023, en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Great_Fire_of_Northampton.

“The borough of Northampton: Description.” A History of the County of Northampton: Volume 3. Ed. William Page. London: Victoria County History, 1930. 30-40. British History Online. Web. http://www.british-history.ac.uk/vch/northants/vol3/pp30-40.

“A History of Northampton.” Local Histories, 14 Mar. 2021, localhistories.org/a-history-of-northampton/.

“All Saints’ Church Northampton.” All Saints’ Church Northampton, http://www.allsaintsnorthampton.co.uk/heritage_all-hallows-church.php.

“History of the Northampton Market | West Northamptonshire Council.” Www.westnorthants.gov.uk, http://www.westnorthants.gov.uk/northampton-market/history-northampton-market.

“The Great Fire of Northampton.” Fraser James Blinds, 25 Nov. 2020, fraserjamesblinds.co.uk/the-great-fire-of-northampton/.

Leave a comment